AB Direct - Steers

Rail: 535.00-539.00 del

AB Direct - Heifers

Rail: 535.00-539.00 del

US Trade- Steers

Rail: 375.00-376.00 * few (IA, NE)

US Trade - Heifers

Rail: 375.00-376.00 * few (IA, NE)

Canadian Dollar

0.39

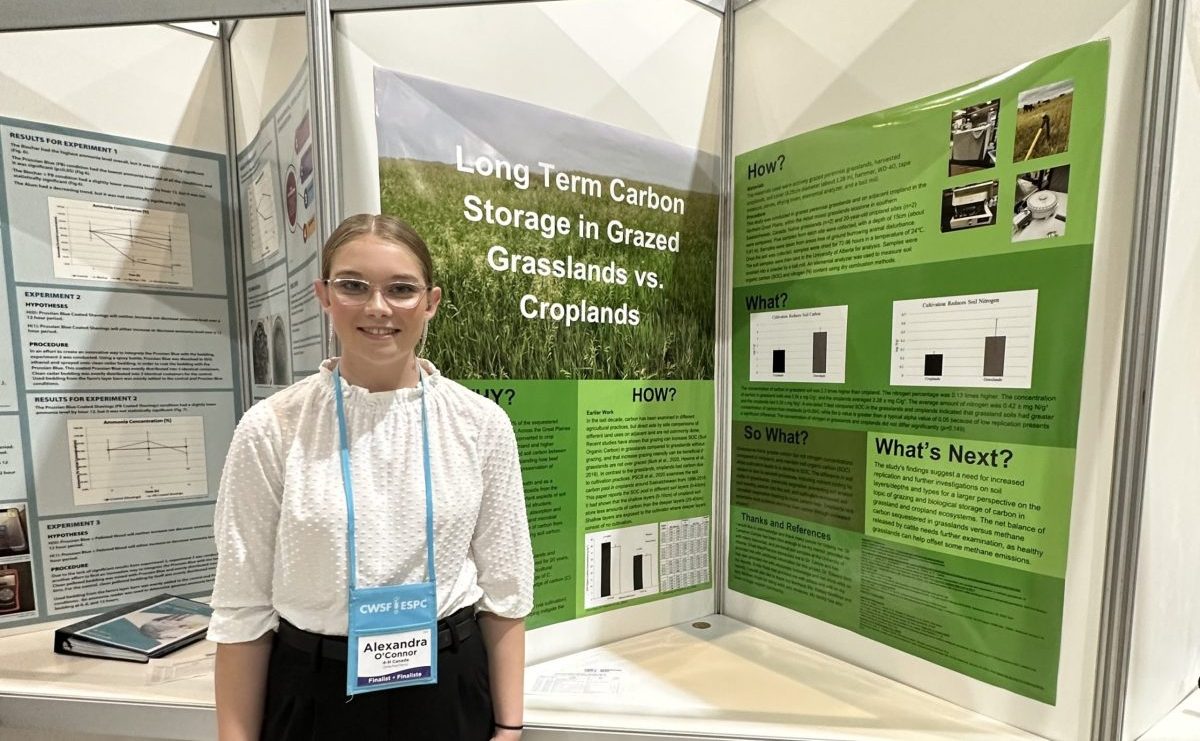

Student’s grassland research shines at Canada-Wide Science Fair

Although Alexandra O’Connor has yet to graduate high school, this young beef producer is already conducting research on the environmental benefits of grasslands.

With the guidance of a university researcher, O’Connor, a fourth-generation purebred producer from Vibank, Saskatchewan, is exploring the long-term carbon storage of grazed grasslands versus croplands. She presented her findings as a student finalist at the 2023 Canada-Wide Science Fair (CWSF) this spring.

“I wanted to get this research out to the public because it’s surprising how many people actually don’t know about agriculture and the role cattle have to play in helping those grasslands,” said O’Connor, who will start Grade 12 this fall.

“I also wanted to show cattle are not a problem to the grasses that they graze or even the land that they graze because there’s a lot of misinformation in the media right now, and I just wanted to promote the correct information,” she continued, adding that she also wanted to share this research with beef and crop producers who want to know more about these concepts.

O’Connor began this project two years ago during a drought, which made her think about how cattle impact grasslands and benefit the soil through grazing. She set out to evaluate the soil organic carbon and nitrogen levels stored in grasslands, then compare those to croplands.

From the field to the lab

Through a connection with the Saskatchewan Stock Growers Association, O’Connor reached out to Cameron Carlyle, Associate Professor at the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Agricultural, Life, and Environmental Sciences. Carlyle’s areas of study are grassland ecology and rangeland ecology and management, making him the ideal mentor for O’Connor’s project.

“He’s been absolutely wonderful to work with because he helps me and guides me, and he’s put a lot of time and effort into helping as well,” she said, noting the impact of working with an academic researcher while still in high school.

“You get a different experience when you work with somebody like that because they have just so much knowledge.”

O’Connor kicked off her project by doing background research using existing academic papers on soil organic carbon in different agricultural land use systems. With that information at hand, she then took soil samples from two of her family’s native pastures and two nearby recently harvested croplands, the latter being cultivated 20 years ago. She collected five soil samples from each site, at a depth of 15 cm.

Each soil sample was dried for 72 to 96 hours before she sent them to the University of Alberta. There, Carlyle analyzed the samples through dry combustion methods, which measured the soil organic carbon and nitrogen.

“I had originally hypothesized that by cattle grazing on grasslands and leaving it undisturbed will hold more carbon (and) nitrogen in the soil, and then in croplands that are harvested and are cultivated…they didn’t hold as much carbon,” O’Connor reported.

The samples proved her hypothesis, with the grassland samples storing 2.3 times more carbon than the cropland samples.

“The difference in soil carbon is due to several processes, including nutrient cycling by cattle in grasslands, perennial vegetation preventing soil erosion and moving carbon into the soil, and cultivation-enhanced soil microbial respiration leading to more carbon loss,” she stated on her project poster. “Croplands lack extensive root systems and may lose carbon through increased erosion.”

Digging deeper

Sharing her project at CWSF in Edmonton was a highlight for O’Connor, whose excitement shone through while recounting this experience. In addition to presenting her research, she met Carlyle in person, toured the University of Alberta, and participated in labs.

“It was a great experience. I learned so much, met very like-minded people, and took home a scholarship,” she said.

“I may have not won a medal, but this experience was an award in itself. Everything that led up to that week was so worth it in the end.”

O’Connor also saw the value of communicating this research to the public, especially with the amount of misinformation circulating about the environmental impact of agriculture. While talking with people about her project, many were unaware of how grasslands sequester great amounts of carbon, and others believed falsehoods around the topic, making it difficult to communicate her findings.

“It was very hard to tell them that my project does stand out and there’s different aspects of looking at things, as well as who does your research as well,” she said.

Her motivation to share these facts with the public increased after attending a youth conference earlier this year, where she heard from a speaker on the public’s lack of understanding of agriculture.

“That’s when I really got an idea of, okay, I need to promote my part of agriculture really well, and I have to do my research really thoroughly because I know these questions are going to come to me eventually,” she explained.

“And they did find their way to me, so I was glad I had gone to that and I was informed about how to not just deal with that but how to handle those kinds of situations.”

O’Connor’s research is just getting started. Next up, she’d like to increase the replications by taking more soil samples, as well as testing different types of soil in different ecoregions, different grazing systems, and pastures grazed by other livestock species.

“I’d also like to test deeper soil layers because different amounts of carbon are stored in the different soil layers,” she said. “When you get to those deeper systems in the native grasslands, they have very deep root systems that can store carbon all the way down to 30 cm.”

In terms of her own next steps, O’Connor is planning to study rangeland ecology at the University of Alberta, and she has her sights set on completing a master’s degree in the future.