AB Direct - Steers

Rail: ---

AB Direct - Heifers

Rail: ---

US Trade- Steers

Rail: ---

US Trade - Heifers

Rail: ---

Canadian Dollar

0.10

Hidden hazards – the challenge with mycotoxins in beef cattle feed

This article was originally posted on the Beef Cattle Research Council’s website on October 9, 2024.

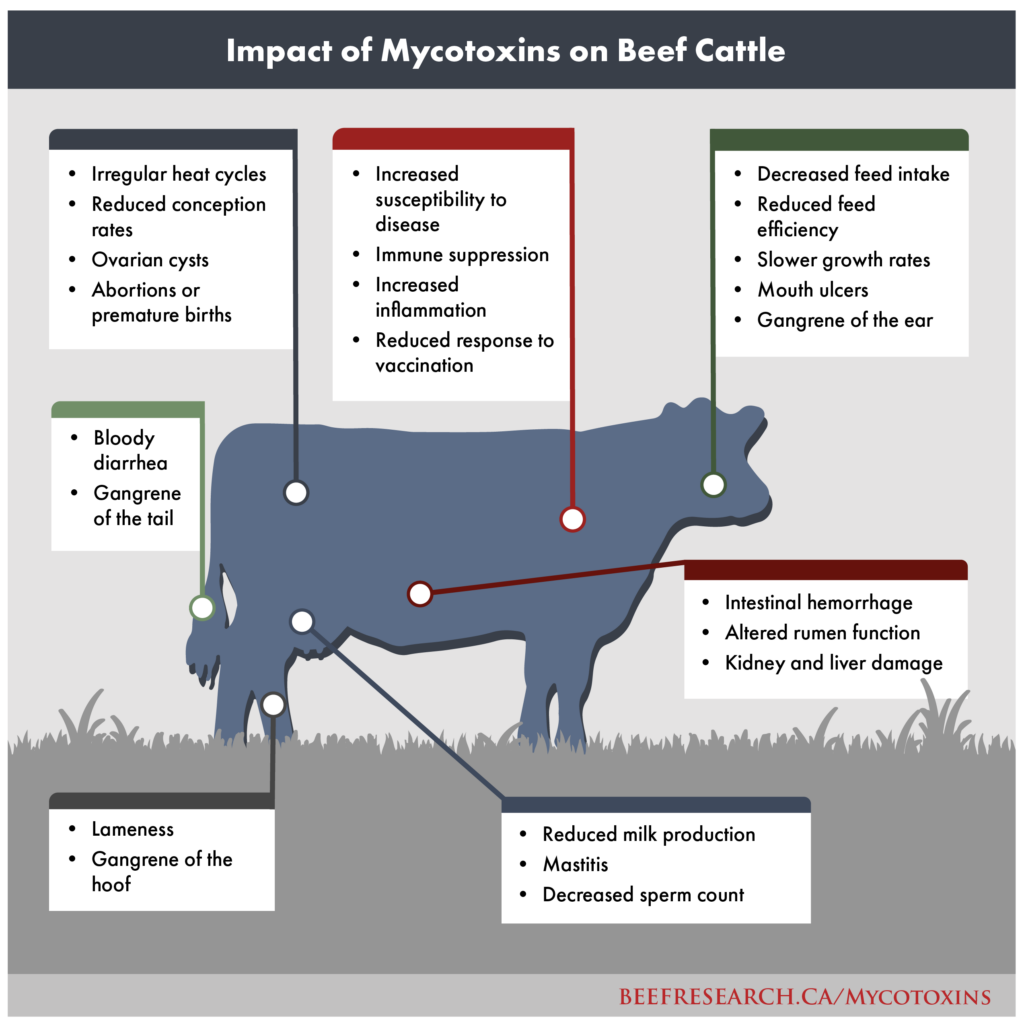

Often hidden hazards in beef cattle diets, mycotoxins can create a variety of problems including impaired immune response which can lead to secondary infections, compromised growth rates, reduced reproductive performance, lameness and gangrene. Illnesses caused by mycotoxins can be difficult to identify and treatment with antibiotics has little to no effect. Therefore, knowing the threat presented by mycotoxins and the appropriate prevention measures to implement are key to reducing the risk to cattle.

What are mycotoxins?

Mycotoxins are produced by certain types of fungi, including mould, and can be present in virtually all of the forages and other feedstuffs that cattle consume. Just because mould or ergot bodies can’t be seen in forage, grain or screenings is no guarantee that mycotoxins aren’t present. These toxins are invisible, colourless and odourless. In addition, the presence of multiple mycotoxins within a single feed can have an increased negative impact on the animal.

The most common sources of mycotoxins that Canadian beef producers encounter are fungal diseases such as Fusarium and ergot, as well as environmental, handling and storage issues that contribute to mouldy feed. The chance of mycotoxins being present in high concentrations in cattle feed can fluctuate substantially in any given year.

When are mycotoxins the biggest risk?

- If feed is suspected to be contaminated, or if conditions have been favourable for mycotoxin production

- If mould is visibly present in a feed being fed to cattle and it makes up a large portion of the diet

- If significant changes in production performance or health are observed in a large percentage of the herd

- If performance or health declines have no obvious cause

What are signs of mycotoxin toxicity in beef cattle?

The symptoms of mycotoxin toxicity will be variable depending on the toxins present, amount ingested, duration of exposure, animal condition and stage of production. These symptoms can include:

- Reduced feed intake: a feed reduction greater than 30% should be investigated

- A decrease in growth or performance, or a failure to thrive

- Animal seems to be frequently sick, which may indicate immune suppression

- Animal does not respond when treated with antibiotics

- Animal has convulsions, muscle spasms or temporary paralysis

- Gangrene or lameness is present, especially in the animal’s ears, tail and feet, which is a sign of ergot toxicity

- Animal shows signs of heat stress, elevated breathing rate, panting or drooling

- Animal has a fever or intermittent bloody diarrhea

- There are blisters, reddening or ulcers in the mouth

- Abortion and premature births occur, or reduced lactation

What can you do to protect your cattle?

Reducing the risk of mycotoxins boils down to four factors:

- awareness,

- feed testing,

- additional best practices for feed quality and

- best practices to keep animals healthy.

Monitor for risk factors which can fluctuate from season to season and year to year, influenced heavily by moisture conditions during growth, harvest and storage. As an example, the risk of Fusarium production is increased with the presence of warm, moist conditions during the flowering stage. In contrast, ergot favors cool, moist conditions during this stage.

When producers are growing their own feed, disease monitoring must include the year before, as risk conditions and pathogen presence can carry over from one year to the next. In the case of ergot, if the fungal bodies are left to mature, they will detach from the plant head and drop to the soil, starting the cycle over again. If the risks are high, consider diverting the crop to silage or cutting early for greenfeed before ergot bodies have developed. For grasses used for feed which may be infected, it is best to mow them sooner rather than later.

Perform regular feed tests on all feeds suspected to be contaminated. Remember mycotoxins and mould are not the same thing. Mycotoxins may be present in a feed even if no mould is visible, therefore, it is difficult to correlate mould or grain damage with the presence of mycotoxins. The only way to know for sure is feed testing for mycotoxin identification.

Ensuring high-quality feed also means following best practices for feed quality at harvest, storage and during feed-out. This includes proper packing to ensure oxygen exclusion for ensiled feeds, managing moisture levels for grains, byproducts and dry forages, and purchasing byproduct feeds from reputable sources, as this type of feed is at an increased risk of contamination.

Healthy animals that are not exposed to stressors are less susceptible to the impact of many mycotoxins. Follow best practices for vaccination, internal and external parasite control, biosecurity, low-stress handling, nutrition and gut health.

Eliminating the threat of mycotoxins is nearly impossible. However, producers can take preventative steps to reduce the possibility of mycotoxin contamination of their feed sources. If mycotoxins are detected in feed, certain strategies can be followed to make the feed source safer for cattle.